(CNN) -- Neil Armstrong, the American astronaut who made "one giant leap for mankind" when he became the first man to walk on the moon, died Saturday. He was 82.

"We are heartbroken to share the news that Neil Armstrong has passed away following complications resulting from cardiovascular procedures," Armstrong's family said in a statement.

Armstrong underwent heart surgery this month.

"While we mourn the loss of a very good man, we also celebrate his remarkable life and hope that it serves as an example to young people around the world to work hard to make their dreams come true, to be willing to explore and push the limits, and to selflessly serve a cause greater than themselves," his family said.

Sen.John Glenn: Armstrong dared greatly

Sen.John Glenn: Armstrong dared greatly  'One giant leap for mankind'

'One giant leap for mankind' 2011: Armstrong among astronauts honored

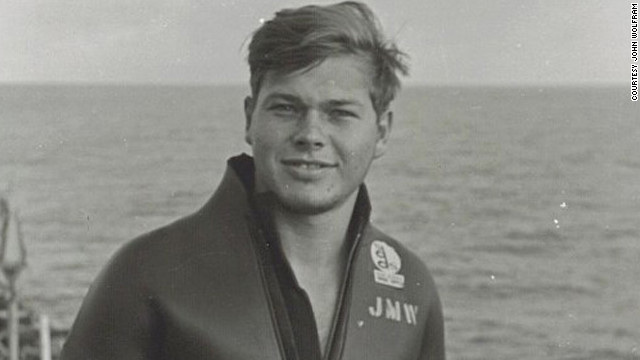

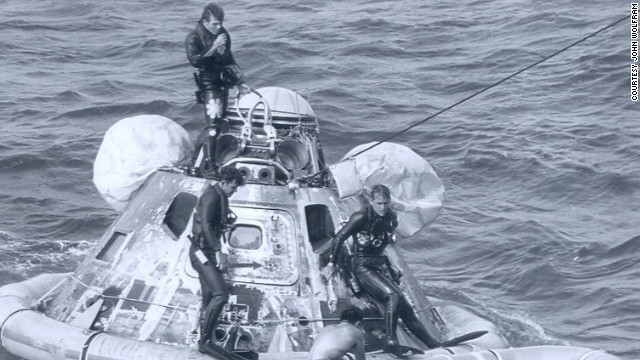

2011: Armstrong among astronauts honored Navy SEALs Wes Chesser, left, and John Wolfram pause after securing the Apollo 11 capsule on July 24, 1969. Wolfram wore 60s "Flower Power" decals, showing his rebellious side. Chesser says, that only now does he realize how physically demanding the mission was. "We were in such good shape."

Navy SEALs Wes Chesser, left, and John Wolfram pause after securing the Apollo 11 capsule on July 24, 1969. Wolfram wore 60s "Flower Power" decals, showing his rebellious side. Chesser says, that only now does he realize how physically demanding the mission was. "We were in such good shape."

At age 20, only two years out of high school, Wolfram was the youngest of an elite team responsible for safely getting the Apollo 11 crew from their capsule to a helicopter. "Being the first to look them in the eye and see that they're OK -- it's quite a rush," Wolfram told CNN.

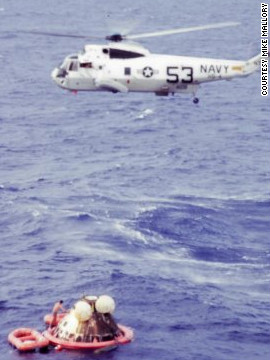

In this U.S. Navy photo, Apollo 11 splashes down about 1,000 miles off Hawaii. It was the exact moment when America achieved President Kennedy's goal to land a man on the moon and return him to Earth, says Scott Carmichael, author of "Moon Men Return." "It's one thing to get the astronauts to the moon, but you've got to bring them back alive."

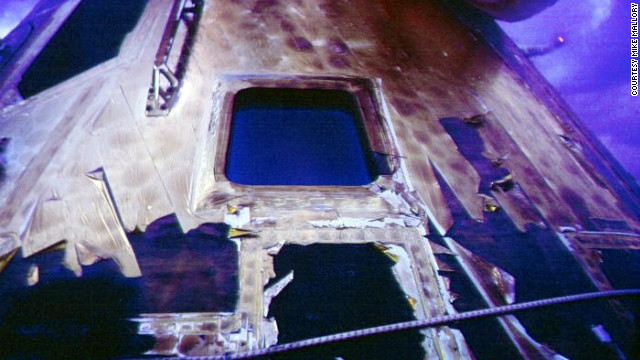

Carmichael described the capsule as "a bobbing, 12-foot high, 12,000-pound, spinning, behemoth" drifting across the ocean current. Frogman Mike Mallory, who snapped many photos of the mission, says he and Wolfram were "muscle guys" who worked against the waves and wind to pull an inflatable ring around the capsule.

After the capsule was stabilized, the astronauts and SEALs put on biological isolation garments to guard against possible lunar pathogens. If the SEALs had been been directly exposed to the astronauts, they would have been ordered to be quarantined.

In the "decontamination raft" mission leader Clancy Hatleberg sprayed the astronauts with sodium hypochlorite and helped them scrub their suits.

Hatleberg helped the astronauts climb into a "Billy-Pugh net" which was used to hoist them into a Navy chopper hovering above.

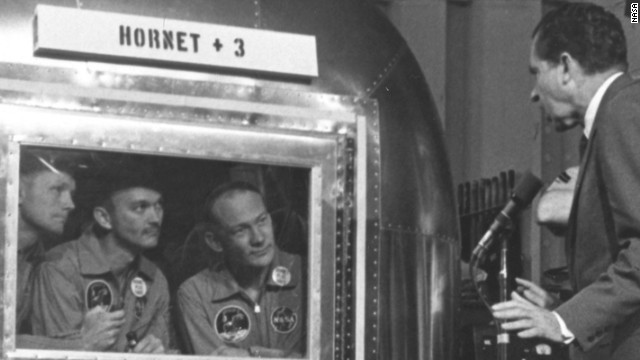

Aboard the aircraft carrier, the trio spoke with President Nixon from inside a trailer where they would be quarantined without incident for 21 days. "I saw you bouncing around in that boat out there," Nixon told them. "I wonder if that wasn't the hardest part of the journey." Armstrong, left, replied, "It was one of the hardest parts."

Back at the capsule, Wolfram and Hatleberg, right, flashed peace signs for Mallory's camera -- which raised eyebrows at the height of the Vietnam War. But Wolfram heard nothing about it from his superiors. "John was a wild, crazy guy," said Mallory. "That was his thing."

The capsule hatch was locked and sealed before the spacecraft was hoisted aboard the Hornet and kept in its own quarantine area, just in case. "We all took strips of that gold foil as souvenirs," said Wolfram.

After two tours in Vietnam, Wolfram returned to the U.S. and had an epiphany during a church service. "That night, my life changed," he says. Now a Georgia-based husband, father and ordained minister, Wolfram serves as a missionary in Southeast Asia.

Wolfram details his adventure in his memoir, "Splashdown." He recently took his family to Washington's Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum where the Apollo 11 capsule is on display.

Mallory, now a husband and grandfather in Michigan, says he was just proud to be a part of the space program as a member of SEAL Team Swim 2. "I wish the space program was continuing better than it is." Chesser, a retired defense contractor, is a newlywed and grandfather living in Virginia. The Space Race "was an extremely exciting time for our country," Chesser says. "Today we don't have that."

Apollo 11: The recovery mission

HIDE CAPTION

Apollo 11: The Recovery

Apollo 11: The Recovery

"As long as there are history books, Neil Armstrong will be included in them," said Charles Bolden. "As we enter this next era of space exploration, we do so standing on the shoulders of Neil Armstrong. We mourn the passing of a friend, fellow astronaut and true American hero."

Armstrong took two trips into space. He made his first journey in 1966 as commander of the Gemini 8 mission, which nearly ended in disaster.

Armstrong kept his cool and brought the spacecraft home safely after a thruster rocket malfunctioned and caused it to spin wildly out of control.

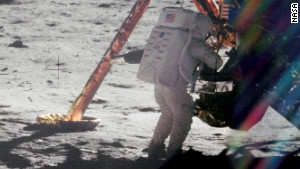

During his next space trip in July 1969, Armstrong and fellow astronauts Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins blasted off in Apollo 11 on a nearly 250,000-mile journey to the moon that went down in the history books. It took them four days to reach their destination.

The world watched and waited as the lunar module "Eagle" separated from the command module and began its descent.

Then came the words from Armstrong: "Tranquility Base here, the Eagle has landed."

About six and a half hours later at 10:56 p.m. ET on July 20, 1969, Armstrong, at age 38, became the first person to set foot on the moon.

He uttered the now-famous phrase: "That's one small step for (a) man, one giant leap for mankind."

The quote was originally recorded without the "a," which was picked up by voice recognition software many years later.

Armstrong was on the moon's surface for two hours and 32 minutes and Aldrin, who followed him, spent about 15 minutes less than that.

The two astronauts set up an American flag, scooped up moon rocks and set up scientific experiments before returning to the main spacecraft.

All three returned home to a hero's welcome, and none ever returned to space.

The moon landing was a major victory for the United States, which at the height of the Cold War in 1961 committed itself to landing a man on the moon and returning him safely before the decade was out.

It was also a defining moment for the world. The launch and landing were broadcast on live TV and countless people watched in amazement as Armstrong walked on the moon.

"I remember very clearly being an 8-year-old kid and watching the TV ... I remember even as a kid thinking, 'Wow, the world just changed,'" said astronaut Leroy Chiao. "And then hours later watching Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin take the very first step of any humans on another planetary body. That kind of flipped the switch for me in my head. I said, 'That's what I want to do, I want to be an astronaut.'"

Tributes to Armstrong -- who received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1969, the highest award offered to a U.S. civilian -- poured in as word of his death spread.

"Neil was among the greatest of American heroes -- not just of his time, but of all time," said President Barack Obama. "When he and his fellow crew members lifted off aboard Apollo 11 in 1969, they carried with them the aspirations of an entire nation. They set out to show the world that the American spirit can see beyond what seems unimaginable -- that with enough drive and ingenuity, anything is possible."

Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney said the former astronaut "today takes his place in the hall of heroes. With courage unmeasured and unbounded love for his country, he walked where man had never walked before. The moon will miss its first son of earth."

House Speaker John Boehner, from Ohio, said: "A true hero has returned to the Heavens to which he once flew. Neil Armstrong blazed trails not just for America, but for all of mankind. He inspired generations of boys and girls worldwide not just through his monumental feat, but with the humility and grace with which he carried himself to the end."

Armstrong was born in Wapakoneta, Ohio, on August 5, 1930. He was interested in flying even as a young boy, earning his pilot's license at age 16, studied aeronautical engineering and earned degrees from Purdue University and University of Southern California. He served in the Navy, and flew 78 combat missions during the Korean War.

"He was the best, and I will miss him terribly," said Collins, the Apollo 11 command module pilot.

After his historic mission to the moon, Armstrong worked for NASA, coordinating and managing the administration's research and technology work. In 1971, he resigned from NASA and taught engineering at the University of Cincinnati for nearly a decade.

While many people are quick to cash in on their 15 minutes of fame, Armstrong largely avoided the public spotlight and chose to lead a quiet, private life with his wife and children.

"He was really an engineer's engineer -- a modest man who was always uncomfortable in his singular role as the first person to set foot on the moon. He understood and appreciated the historic consequences of it and yet was never fully willing to embrace it. He was modest to the point of reclusive. You could call him the J.D. Salinger of the astronaut corps," said Miles O'Brien, an aviation expert with PBS' Newshour, formerly of CNN.

"He was a quiet, engaging, wonderful from the Midwest kind of guy. ... But when it came to the public exposure that was associated with this amazing accomplishment ... he ran from it. And part of it was he felt as if this was an accomplishment of many thousands of people. And it was. He took the lion's share of the credit and he felt uncomfortable with that," said O'Brien.

But Armstrong always recognized -- in a humble manner -- the importance of what he had accomplished.

"Looking back, we were really very privileged to live in that thin slice of history where we changed how man looks at himself and what he might become and where he might go," Armstrong said.

At age 20, only two years out of high school, Wolfram was the youngest of an elite team responsible for safely getting the Apollo 11 crew from their capsule to a helicopter. "Being the first to look them in the eye and see that they're OK -- it's quite a rush," Wolfram told CNN.

At age 20, only two years out of high school, Wolfram was the youngest of an elite team responsible for safely getting the Apollo 11 crew from their capsule to a helicopter. "Being the first to look them in the eye and see that they're OK -- it's quite a rush," Wolfram told CNN.

In this U.S. Navy photo, Apollo 11 splashes down about 1,000 miles off Hawaii. It was the exact moment when America achieved President Kennedy's goal to land a man on the moon and return him to Earth, says Scott Carmichael, author of "Moon Men Return." "It's one thing to get the astronauts to the moon, but you've got to bring them back alive."

In this U.S. Navy photo, Apollo 11 splashes down about 1,000 miles off Hawaii. It was the exact moment when America achieved President Kennedy's goal to land a man on the moon and return him to Earth, says Scott Carmichael, author of "Moon Men Return." "It's one thing to get the astronauts to the moon, but you've got to bring them back alive."

Carmichael described the capsule as "a bobbing, 12-foot high, 12,000-pound, spinning, behemoth" drifting across the ocean current. Frogman Mike Mallory, who snapped many photos of the mission, says he and Wolfram were "muscle guys" who worked against the waves and wind to pull an inflatable ring around the capsule.

Carmichael described the capsule as "a bobbing, 12-foot high, 12,000-pound, spinning, behemoth" drifting across the ocean current. Frogman Mike Mallory, who snapped many photos of the mission, says he and Wolfram were "muscle guys" who worked against the waves and wind to pull an inflatable ring around the capsule.

After the capsule was stabilized, the astronauts and SEALs put on biological isolation garments to guard against possible lunar pathogens. If the SEALs had been been directly exposed to the astronauts, they would have been ordered to be quarantined.

After the capsule was stabilized, the astronauts and SEALs put on biological isolation garments to guard against possible lunar pathogens. If the SEALs had been been directly exposed to the astronauts, they would have been ordered to be quarantined.

In the "decontamination raft" mission leader Clancy Hatleberg sprayed the astronauts with sodium hypochlorite and helped them scrub their suits.

In the "decontamination raft" mission leader Clancy Hatleberg sprayed the astronauts with sodium hypochlorite and helped them scrub their suits.

Hatleberg helped the astronauts climb into a "Billy-Pugh net" which was used to hoist them into a Navy chopper hovering above.

Hatleberg helped the astronauts climb into a "Billy-Pugh net" which was used to hoist them into a Navy chopper hovering above.

Aboard the aircraft carrier, the trio spoke with President Nixon from inside a trailer where they would be quarantined without incident for 21 days. "I saw you bouncing around in that boat out there," Nixon told them. "I wonder if that wasn't the hardest part of the journey." Armstrong, left, replied, "It was one of the hardest parts."

Aboard the aircraft carrier, the trio spoke with President Nixon from inside a trailer where they would be quarantined without incident for 21 days. "I saw you bouncing around in that boat out there," Nixon told them. "I wonder if that wasn't the hardest part of the journey." Armstrong, left, replied, "It was one of the hardest parts."

Back at the capsule, Wolfram and Hatleberg, right, flashed peace signs for Mallory's camera -- which raised eyebrows at the height of the Vietnam War. But Wolfram heard nothing about it from his superiors. "John was a wild, crazy guy," said Mallory. "That was his thing."

Back at the capsule, Wolfram and Hatleberg, right, flashed peace signs for Mallory's camera -- which raised eyebrows at the height of the Vietnam War. But Wolfram heard nothing about it from his superiors. "John was a wild, crazy guy," said Mallory. "That was his thing."

The capsule hatch was locked and sealed before the spacecraft was hoisted aboard the Hornet and kept in its own quarantine area, just in case. "We all took strips of that gold foil as souvenirs," said Wolfram.

The capsule hatch was locked and sealed before the spacecraft was hoisted aboard the Hornet and kept in its own quarantine area, just in case. "We all took strips of that gold foil as souvenirs," said Wolfram.

After two tours in Vietnam, Wolfram returned to the U.S. and had an epiphany during a church service. "That night, my life changed," he says. Now a Georgia-based husband, father and ordained minister, Wolfram serves as a missionary in Southeast Asia.

After two tours in Vietnam, Wolfram returned to the U.S. and had an epiphany during a church service. "That night, my life changed," he says. Now a Georgia-based husband, father and ordained minister, Wolfram serves as a missionary in Southeast Asia.

Wolfram details his adventure in his memoir, "Splashdown." He recently took his family to Washington's Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum where the Apollo 11 capsule is on display.

Wolfram details his adventure in his memoir, "Splashdown." He recently took his family to Washington's Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum where the Apollo 11 capsule is on display.

Mallory, now a husband and grandfather in Michigan, says he was just proud to be a part of the space program as a member of SEAL Team Swim 2. "I wish the space program was continuing better than it is." Chesser, a retired defense contractor, is a newlywed and grandfather living in Virginia. The Space Race "was an extremely exciting time for our country," Chesser says. "Today we don't have that."

Mallory, now a husband and grandfather in Michigan, says he was just proud to be a part of the space program as a member of SEAL Team Swim 2. "I wish the space program was continuing better than it is." Chesser, a retired defense contractor, is a newlywed and grandfather living in Virginia. The Space Race "was an extremely exciting time for our country," Chesser says. "Today we don't have that."