Friday, December 28, 2012

Friday, December 21, 2012

Monday, December 17, 2012

Friday, December 14, 2012

Love is "One Hour with You"!

Being in my film library and watched a thousand times, it never fails the funny bone and intellect that there's a Colette and Andre, Mitzi and Adolph in all of us!

The dashing Andre (Maurice Chevalier) must overcome temptation when his wife Colette's (Jeanette MacDonald) beautiful best friend, Mitzi (Genevieve Tobin), tries to seduce him. Meanwhile, suspecting his wife of infidelity, Mitzi's disgruntled husband (Roland Young) begins pursuing Colette. Directed by the matchless Ernst Lubitsch, this musical romp, set in Paris, was nominated for the Best Picture Oscar in 1932.

The film is a musical remake of The Marriage Circle (1924), the second film that Lubistch made in the United States and in 1932 was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture. The French version, Une heure près de toi, was made simultaneously with Lili Damita playing Genevieve Tobin's role.

The film is a musical remake of The Marriage Circle (1924), the second film that Lubistch made in the United States and in 1932 was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture. The French version, Une heure près de toi, was made simultaneously with Lili Damita playing Genevieve Tobin's role.

Tuesday, December 11, 2012

Looming Health Crisis in the Rockaways, New York after Hurricane Sandy

CNN PRODUCER NOTE DougKuntz, a freelance photojournalist in New York, read about humanitarian volunteer Alison Thompson in a story about Hurricane Sandy, and learned about her past with other disasters around the world. 'I came to Rockaway and followed her around while she worked. She is a modern-day hero in my eyes.' Kuntz wanted to share her story with CNN 'because the problems in Rockaway are growing, and are not being reported as they should be.'

Third Wave Volunteer and Medic, Alison Thompson, who has jumped head

first into some of the world's worst scenes of death including 9-11, the earthquake in Haiti, and the Tsunami in Sri Lanka, gives her take on the looming health crisis in the Rockaways where there is not enough help at this time to avoid serious health issues for thousands of residents.

Thompson is a full time humanitarian volunteer, who in 2010, was awarded the Order of Australia, the highest civilian medal awarded by Queen Elizabeth II of England for her volunteer work and contribution to humankind.

Alison Thompson's voice should be heard now while there is still time.

Thompson is a full time humanitarian volunteer, who in 2010, was awarded the Order of Australia, the highest civilian medal awarded by Queen Elizabeth II of England for her volunteer work and contribution to humankind.

Alison Thompson's voice should be heard now while there is still time.

Sunday, December 9, 2012

Saturday, December 1, 2012

"Nights of Cabiria" and "La Strada," my favorites of Federico Fellini's fertile imagination

How can a screenwriter, director, actor, audience member not love everything by el maestro, Federico Fellini, and his lovely wife, Giuletta Masina. Nights of Cabiria and La Strada, my favorites, will touch even the most cynical of hearts.

p.s. and the music by Nino Rota, exquisite!

Despite an endless string of heartbreaks and misfortune, Cabiria (Giulietta

Masina), a wide-eyed prostitute working the streets of Rome, never seems to give

up on finding true love. One of director Federico Fellini's best-known efforts,

this supremely human tale -- by turns absurdly comic and jarringly tragic -- won

the Oscar for Best Foreign Film, and the visually arresting Masina earned Best

Actress honors at the Cannes Film Festival.

Filmmaker Martin Scorsese introduces this restored special edition of Italian auteur Federico Fellini's powerful rumination on love and hate, which won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film in 1956. The story follows the plight of gentle Gelsomina (Giulietta Masina), who's sold by her mother to a bullying circus performer (Anthony Quinn), only to have a clown (Richard Basehart) win her heart and ignite a doomed love triangle.

http://whoseroleisitanyway.blogspot.com

Saturday, November 24, 2012

RIVERS AND TIDES -- The wonder of sculpting with nature

This is an extraordinary documentary of sculptor Andy Goldsworthy's work. In 1 1/2 hrs, have learned more about the rhythm of earth through his art and sensibilities. Wonderful!

This astonishing documentary from Thomas Riedelsheimer shadows renowned sculptor Andy Goldsworthy as he creates works of art with ice, driftwood, leaves, stone, dirt and snow in open fields, beaches, rivers, creeks and forests.

With each new creation, he carefully studies the energetic flow and transitory nature of his work. The film won the Golden Gate Award Grand Prize for Best Documentary at the 2003 San Francisco International Film Festival.

http://whoseroleisitanyway.blogspot.com

Monday, November 19, 2012

Wednesday, November 14, 2012

TREND CAR OF THE YEAR by Peter Valdes-Dapena

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) -- Motor Trend magazine has named the Tesla Model S its Car of the Year.

The magazine's staff selected the all-electric plug-in luxury car out of a field of 11 finalists that included models such as the Ford Fusion, Porsche 911 and Hyundai Azera.

It is the first time the magazine's Car of the Year award has ever gone to an all-electric car. Just being electric wasn't enough to earn the Model S the prize, though. Ed Loh, Motor Trend's editor-in-chief on Monday said that, with eleven finalists, it was a strong field this year. But in the end there was no question about who the winner was. "The vehicles that placed second and third didn't get more than three votes. But it was a unanimous decision for the Tesla Model S." "At its core, the Tesla Model S is simply a damned good car you happen to plug in to refuel," editor-at-large Angus MacKenzie wrote in an article about the award.

Motor Trend calls the Model S "as smoothly effortless as a Rolls-Royce" to drive fast while having the cargo and passenger capacity of an SUV. The Model S was one of the most efficient cars the magazine has ever tested, averaging 74.5 miles per gallon equivalent -- a measure of how far the car goes on an amount of electricity equivalent to the energy in a gallon of gasoline -- during ordinary street driving. Still, the big car can bolt from a standstill to 60 miles an hour in just four seconds, according to Motor Trend's tests.

At the New York City announcement ceremony Tesla CEO Elon Musk said, "This is a point at which the gears of history moved," adding, "I hope that other automakers will copy us and follow through and do electric cars with more vigor." To be eligible for Motor Trend's Car of the Year award a vehicle must be, first of all, a car rather than an SUV or truck. The magazine gives separate truck and SUV awards. It also must be either completely new or substantially redesigned for the new model year. In all there were 25 models competing for the award this year. After testing all the models at the Hyundai/Kia proving grounds in the southwest California desert, the magazine's staffers narrowed the list to just 11 finalists. Those cars were then tested on roads and highways around the town of Tehachapi, Calif.

After further debate, the writers and editors selected the winner through a secret ballot. It's impossible to say if the Model S would have won had it been a standard gasoline-powered luxury car, said McKenzie. That's because it would have been a different car in nearly every respect. Its strong, quiet performance is attributable to its electric motors while its roomy interior is thanks to the design flexibility they provide. The Model S can hold up to seven people when equipped with an optional pair of rear-facing child seats. Since there is no engine, both the back and front of the car can be used for cargo, giving it functionality very similar to an SUV. The Model S ranges from $50,000 for a car that can go 160 miles on a charge to almost $100,000 for a richly equipped model that can go 300 miles. It went into production this summer, and by the beginning of October Tesla said it had sold about 250 Model S sedans. It expects to sell about 3,200 by end of this year.

Labels:

electric car,

Motor Trend magazine,

Tesla Model S

Wednesday, November 7, 2012

May the beacon of hope, courage, and strength guide you through these difficult times:

The Bahamas

Cuba

The Dominican Republic

Haiti

Jamaica, Greater Antilles

United States

New Jersey

New York

...from Florida to Maine, Michigan to Wisconsin

Labels:

Hurricane Sandy

Saturday, October 27, 2012

George Nolfi's "The Adjustment Bureau" based upon Phillip K. Dick's short story "The Adjustment Team"

Based on master science-fiction writer Phillip K. Dick's, The Adjustment Team, with his usual theme of metaphysics parallel to reality, is captured wonderfully by writer, director George Nolfi.

Synopsis: A congressman (Matt Damon) who's a rising star on the political scene finds himself entranced by a beautiful ballerina (Emily Blunt), but mysterious circumstances ensure that their love affair is predestined to be a non-starter. Screenwriter George Nolfi (The Bourne Ultimatum) makes his directorial debut with this romantic adaptation of Phillip K. Dick's classic sci-fi short story "Adjustment Team."

Labels:

phillip dick,

science fiction,

the adjustment bureau

Sunday, October 14, 2012

SUNDAY IS FOR POETRY: Life

Minimal possessions --

Splashes of rainforests

Panoramic heavens

Oceans of desert

Stampeding animals

Trees of music

All of creation.

Life.

Saturday, October 6, 2012

The dialect, spoken in the Scottish village Cromarty, appears to be the only Germanic descendant without "wh" pronunciation.

(CNN) -- Bobby Hogg, the last native speaker of a dialect originating from a remote fishing village in northern Scotland, has died -- and so has the dialect he spoke.

The death of the 92-year-old

retired engineer means that the Scots dialect known as Cromarty fisherfolk is

now consigned to a collection of brief, distorted audio clips.

It is the first unique dialect to

be lost in Scotland, according to Robert Millar, a reader in linguistics at the

School of Language and Literature at Aberdeen University.

"Usually minority dialects end up

blending in with standard English to form a hybrid. However, this is a

completely distinct dialect which has become extinct," he said.

Cromarty fisherfolk appears to be

the only descendant from the Germanic linguistic world in which no "wh"

pronunciation existed, Millar said.

"'What' would become 'at' and

'where' would just be 'ere'," he said.

It was also the Scots language's

only dialect that dropped the "H" aspiration.

"The loss of Cromarty is

symptomatic of a greater, general decline in the use of the Scots language,"

according to Director of Scottish Language Dictionaries Chris Robinson. "This

should be a wake-up call to save other struggling dialects."

Ten miles down the coast from

Cromarty is Avoch, another sleepy fishing village with the closest surviving

dialect to Cromarty fisherfolk, one that may also be endangered, according to

Robinson. "It looks more than likely that this will go the same way as the

Cromarty dialect," he said.

The dialect of the peoples who

originally resided on the shores of Cromarty -- which lies on the tip of Black

Isle peninsula, a four-hour drive north of Edinburgh -- was directly linked to

their traditional fishing methods.

However, during the

industrialization of fishing in the 1950s, established working methods were lost

and the connection between the way of life and the dialect eroded. In fewer than

30 years, much of the dialect became obsolete.

Millar argues that the decline

in Scots language represents a wider global trend.

"Generally, in the literate

world, local dialects are suffering. The highly mobile and technologically

advanced areas of the world are worst affected," he said.

There are some 6,000 to 7,000

languages in the world and it is estimated that they are disappearing at a rate

of one every two weeks, according to Millar.

Some 96% of the world's

population speak just 4% of the world's languages, he said. "Most languages are

only spoken by a few hundred people," he added.

Why mourn the loss of a

language? "At a banal level, it's a little bit of color in our lives is gone,"

he said. "Any time something dies, it's lost. Whether it be languages or

species, we lose something. Everyone in the world loses something. Diversity

surely is a good thing, and we've just lost a bit of it."

Greater communication and

interdependence among communities is resulting in "dialect homogenization,"

Millar said.

And people tend to abandon their

own languages for one of the larger languages for good reasons, according to

Anthony Aristar, professor of linguistics at Eastern Michigan University and

director of the school's Institute for Language Information and Technology.

"They want modern conveniences;

they want their children to have decent jobs," he told CNN in a telephone

interview. "All this requires being able to speak in the dominant language. So

they see little use in preserving their languages."

But the loss of a language often

results in the loss of the stories that were told in that language, and in the

cultural knowledge they contained. "Even medical know-how," he said.

Robinson, of the Scottish

Language Dictionaries, maintains that Scots minority dialects like Cromarty have

faced other pressures.

"Educationally, English has been

the language used in Scotland since the 18th century. Consequently, Scots

speakers are not literate in their own language. Also, until recently, Scots has

had a social stigma attached to it as a working-class or second-rate

language."

Yet there are signs of

improvement for the state of Scots minority dialects. More Scots books,

especially children's books, are being published than ever before. In addition,

since 2009, the Scottish government has provided funding for the Scottish

Language Dictionaries, which has also given the language a status boost.

The support has been seen as a

natural progression from the move by Westminster in 2002 to sign the European

Union Charter of Minority and Regional Languages recognizing Scots, Gaelic and

Welsh as languages separate from English.

Still, the rate of the worldwide

loss of dialects and languages remains consistent.

Robinson said he would like to

see more efforts taken to safeguard minority Scots dialects.

"Scots has an amazing literary

history, yet it is completely ignored in our schools," he said. "The books must

be made more widely available and read more in schools for the language to

survive in the future."

http://whoseroleisitanyway.blogspot.com

http://whoseroleisitanyway.blogspot.com

Labels:

cromarty fisherfolk,

dialects,

Scotland

Friday, September 21, 2012

Saturday, September 15, 2012

WHAT THE BRAIN DRAWS FROM: Art and Neuroscience by Elizabeth Landau

Leonardo da Vinci took advantage of the differences in the human central and peripheral visual systems to create a dynamic smile in the "Mona Lisa."

(CNN) -- Pablo Picasso once said, "We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand. The artist must know the manner whereby to convince others of the truthfulness of his lies." If we didn't buy in to the "lie" of art, there would obviously be no galleries or exhibitions, no art history textbooks or curators; there would not have been cave paintings or Egyptian statues or Picasso himself.

Yet, we seem to agree as a species that it's possible to recognize familiar things in art and that art can be pleasing. To explain why, look no further than the brain. The human brain is wired in such a way that we can make sense of lines, colors and patterns on a flat canvas. Artists throughout human history have figured out ways to create illusions such as depth and brightness that aren't actually there but make works of art seem somehow more real. And while individual tastes are varied and have cultural influences, the brain also seems to respond especially strongly to certain artistic conventions that mimic what we see in nature.

What we recognize in art

It goes without saying that most paintings and drawings are, from an objective standpoint, two-dimensional. Yet our minds know immediately if there's a clear representation of familiar aspects of everyday life, such as people, animals, plants, food or places. And several elements of art that we take for granted trick our brains into interpreting meaning from the arbitrary.

Lines

For instance, when you look around the room in which you're sitting, there are no black lines outlining all of the objects in your view; yet, if someone were to present you with a line-drawing of your surroundings, you would probably be able to identify it.

This concept of line drawings probably dates back to a human ancestor tracing lines in the sand and realizing that they resembled an animal, said Patrick Cavanagh, professor at Universite Paris Descartes.

"For science, we're just fascinated by this process: Why things that are not real, like lines, would have that effect," Cavanagh said. "Artists do the discoveries, and we figure out why those tricks work." That a line drawing of a face can be recognized as a face is not specific to any culture. Infants and monkeys can do it. Stone Age peoples did line drawings; the Egyptians outlined their figures, too. It turns out that these outlines tap into the same neural processes as the edges of objects that we observe in the real world. The individual cells in the visual system that pick out light-dark edges also happen to respond to lines, Cavanagh said. We'll never know who was the first person to create the first "sketch," but he or she opened the avenue to our entire visual culture.

Faces

This brings us to modern-day emoticons; everyone can agree that this :-) is a sideways happy face, even though it doesn't look like any particular person and has only the bare minimum of facial features.

Our brains have a special affinity for faces and for finding representations of them (some say they see the man in the moon, for instance). Even infants have been shown in several studies to prefer face-like patterns over patterns that don't resemble anything. A sculpture of Catalan painter Joan Miro by Alexander Calder shows Miro's face only in outlines.That makes sense from an evolutionary perspective: It benefits babies to establish a bond with their caregivers early on, notes Mark H. Johnson in a 2001 Nature Reviews Neuroscience article. Our primitive human ancestors needed to be attuned to animals around them; those who were most aware of potential predators would have been more likely to survive and pass on their genes.

So our brains readily find faces in art, including in Impressionist paintings where faces are constructed from colored lines or discrete patches of color. This "coarse information" can trigger emotional responses, even without you bearing aware of it, Cavanagh and David Melcher write in the essay "Pictorial Cues in Art and in Visual Perception." Patrik Vuilleumier at the University of Geneva and colleagues figured out that the amygdala, a part of the brain involved in emotions and the "flight or fight response," responds more to blurry photos of faces depicting fear than unaltered or sharply detailed images.

At the same time, the part of our brain that recognizes faces is less engaged when the face is blurry. Cavanagh explains that this may mean we are more emotionally engaged when the detail-oriented part of our visual system is distracted, such as in Impressionist works where faces are unrealistically colorful or patchy.

Color vs. luminance

Artists also play with the difference between color and luminance. Most people have three kinds of cones in the eye's retina: red, blue and green. You know what color you're looking at because your brain compares the activities in two or three cones.

A different phenomenon, called luminance, adds the activities from the cones together as a measure of how much light appears to be passing through a given area. Usually when there is color contrast, there is also luminance contrast, but not always.

In the research of Margaret Livingstone, professor of neurobiology at Harvard University, she explored the painting "Impression Sunrise" by Claude Monet, which features a shimmering sun over water. Although the orange sun appears bright, it objectively has the same luminance as the background, Livingstone found. So why does it look so bright to the human eye? Livingstone explained in a 2009 lecture at the University of Michigan that there are two major processing streams for our visual system, which Livingstone calls the "what" and "where" streams. The "what" allows us to see in color and recognize faces and objects. The "where" is a faster and less detail-oriented but helps us navigate our environment but is insensitive to color.

When our brains recognize a color contrast but no light contrast, that's called "equal luminance," and it creates a sort of shimmering quality, Livingstone said. And that's what's going on in a Monet painting. Artists often play with luminance in order to give the illusion of three dimensions, since the range of luminance in real life is far greater than what can be portrayed in a painting, Livingstone said. By placing shadows and lights that wouldn't be present in real life, paintings are able to trick the eye into perceiving depth. In an icon by an artist of the Moscow School from about 1450, the Virgin Mary does not have a lot of depth.

For instance, medieval paintings portrayed the Virgin Mary in a dark blue dress, which makes her look flat. Leonardo da Vinci, however, revolutionized her appearance by adding extra lights to contrast with darks. The bottom line: To trick the brain into thinking something looks three-dimensional and lifelike, artists add elements -- lightness and shadows -- that wouldn't be present in real life but that tap into our hard-wired visual sensibilities.

Mona Lisa's smile

The Mona Lisa is undoubtedly one of the world's most famous paintings; the face of the woman in the painting is iconic. Da Vinci gave her facial expression a dynamic quality by playing with a discrepancy that exists in our peripheral and central vision systems, Livingstone says. The human visual system is organized such that the center of gaze is specialized for small, detailed things, and the peripheral vision has a lower resolution -- it's better at big, blurry things.

That's why, as your eyes move around the Mona Lisa's face, her expression appears to change, Livingstone says. The woman was painted such that, looking directly at the mouth, she appears to smile less than when you're staring into her eyes. When you look away from the mouth, your peripheral visual system picks up shadows from her cheeks that appear to extend the smile.

Photomosaics also take advantage of this difference between visual systems. With your peripheral visual system you might see a picture of a cat that's composed of individual photos of cats that are completely different.

Shadows and mirrors

From a scientific standpoint, it's possible to determine exactly how shadows are supposed to look based on the placements of light and how mirror reflections appear at given angles. But the brain doesn't perform such calculations naturally. It turns out that we don't really notice when shadows in paintings are unrealistically placed, unless glaringly so, or when mirrors don't work exactly the way they do in real life, Cavanagh explained in a 2005 article in "Nature."

Shadows are colored more darkly than what's around them; it's not readily apparent if the lighting direction is inconsistent. They can even be the wrong shape; as long as they don't look opaque, they help convince us of a three-dimensional figure. Studies have shown that people don't generally have a good working knowledge of how reflections should appear, or where, in relation to the original object, Cavanagh said. Paintings with people looking into mirrors or birds reflected in ponds have been fooling us for centuries.

Why we like art

There are certain aspects of art that seem universally appealing, regardless of the environment or culture in which you grew up, argues V.S. Ramachandran, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Diego. He discusses these ideas in his recent book "The Tell Tale Brain."

Symmetry, for instance, is widely considered to be beautiful. There's an evolutionary reason for that, he says: In the natural world, anything symmetrical is usually alive. Animals, for instance, have symmetrical shapes. That we find symmetry artistically appealing is probably based on a hard-wired system meant to alert us to the possibility of a living thing, he said.

Can you fool the brain? And then there's what Ramachandran calls the "peak shift principle." The basic idea is that animals attracted to a particular shape will be even more attracted to an exaggerated version of that form. This was shown in an experiment by Niko Tinbergen involving Herring seagull chicks. In a natural environment, the chick recognizes its mother by her beak. Mommy seagull beaks are yellow with a red spot at the end. So if you wave an isolated beak in front of a chick, it believes the disembodied beak is the mother and taps it as a way of asking to be fed. But even more striking, if you have a long yellow stick with a red stripe on it, the chick still begs for food. The red spot is the trigger that tells the chick this is the mother who will feed it. Now here's the crazy part: the chick is even more excited if the stick has multiple red stripes. The point of the seagull experiment is that although the actual mother's beak is attractive to the chick, a "super beak" that exaggerates the original beak hyperactivates a neural system. "I think you're seeing the same thing with all kinds of abstract art," Ramachandran said. "It looks distorted to the eye, but pleasing to the emotional center to the brain." In this self portrait, Vincent van Gogh distorts his own face with his signature style, which may increase its appeal.In other words, the distorted faces of famous artists such as Pablo Picasso and Gustav Klimt may be hyperactivating our neurons and drawing us in, so to speak. Impressionism, with its soft brushstrokes, is another form of distortion of familiar human and natural forms.

Further research

Can we know what is art? There's now a whole field called neuroesthetics devoted to the neural basis of why and how people appreciate art and music and what is beauty. Semir Zeki at University College London is credited with establishing this discipline, and says it's mushrooming.

Many scientists who study emotion are collaborating in this area. Zeki is studying why people tend prefer certain patterns of moving dots to others. Stanford Journal of Neuroscience: The Neuroscience of Art There have been several criticisms about neuroesthetics as a field.

Philosopher Alva Noe wrote in The New York Times last year that this branch of science has not produced any interesting or surprising insights, and that perhaps it won't because of the very nature of art itself -- how can anyone ever say definitively what it is?

Zeki said many challenges against his field are based on the false assumption that he and colleagues are trying to explain works of art. "We're not trying to explain any work of art," he said. "We're trying to use works of art to understand the brain."

Neuroscientists can make art, too. Zeki had works in an exhibit that opened last year in Italy called "White on White: Beyond Malevich." The series included white painted sculptures on white walls, illuminated by white light and color projections. With red and white light, the shadow of the object appears in the complimentary color -- green -- and the shadows change as your angle of vision changes. The biological basis for this complimentary color effect is not well understood, nor is the depth of shadow, which is also an illusion. So was Picasso right -- is art a lie? The description of Zeki's exhibition in Italy may highlight the truth: "Our purpose is to show how the brain reality even overrides the objective reality."

~~~~~~~

In my opinion: We tend to overanalyze...

(CNN) -- Pablo Picasso once said, "We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand. The artist must know the manner whereby to convince others of the truthfulness of his lies." If we didn't buy in to the "lie" of art, there would obviously be no galleries or exhibitions, no art history textbooks or curators; there would not have been cave paintings or Egyptian statues or Picasso himself.

Yet, we seem to agree as a species that it's possible to recognize familiar things in art and that art can be pleasing. To explain why, look no further than the brain. The human brain is wired in such a way that we can make sense of lines, colors and patterns on a flat canvas. Artists throughout human history have figured out ways to create illusions such as depth and brightness that aren't actually there but make works of art seem somehow more real. And while individual tastes are varied and have cultural influences, the brain also seems to respond especially strongly to certain artistic conventions that mimic what we see in nature.

What we recognize in art

It goes without saying that most paintings and drawings are, from an objective standpoint, two-dimensional. Yet our minds know immediately if there's a clear representation of familiar aspects of everyday life, such as people, animals, plants, food or places. And several elements of art that we take for granted trick our brains into interpreting meaning from the arbitrary.

Lines

For instance, when you look around the room in which you're sitting, there are no black lines outlining all of the objects in your view; yet, if someone were to present you with a line-drawing of your surroundings, you would probably be able to identify it.

This concept of line drawings probably dates back to a human ancestor tracing lines in the sand and realizing that they resembled an animal, said Patrick Cavanagh, professor at Universite Paris Descartes.

"For science, we're just fascinated by this process: Why things that are not real, like lines, would have that effect," Cavanagh said. "Artists do the discoveries, and we figure out why those tricks work." That a line drawing of a face can be recognized as a face is not specific to any culture. Infants and monkeys can do it. Stone Age peoples did line drawings; the Egyptians outlined their figures, too. It turns out that these outlines tap into the same neural processes as the edges of objects that we observe in the real world. The individual cells in the visual system that pick out light-dark edges also happen to respond to lines, Cavanagh said. We'll never know who was the first person to create the first "sketch," but he or she opened the avenue to our entire visual culture.

Faces

This brings us to modern-day emoticons; everyone can agree that this :-) is a sideways happy face, even though it doesn't look like any particular person and has only the bare minimum of facial features.

Our brains have a special affinity for faces and for finding representations of them (some say they see the man in the moon, for instance). Even infants have been shown in several studies to prefer face-like patterns over patterns that don't resemble anything. A sculpture of Catalan painter Joan Miro by Alexander Calder shows Miro's face only in outlines.That makes sense from an evolutionary perspective: It benefits babies to establish a bond with their caregivers early on, notes Mark H. Johnson in a 2001 Nature Reviews Neuroscience article. Our primitive human ancestors needed to be attuned to animals around them; those who were most aware of potential predators would have been more likely to survive and pass on their genes.

So our brains readily find faces in art, including in Impressionist paintings where faces are constructed from colored lines or discrete patches of color. This "coarse information" can trigger emotional responses, even without you bearing aware of it, Cavanagh and David Melcher write in the essay "Pictorial Cues in Art and in Visual Perception." Patrik Vuilleumier at the University of Geneva and colleagues figured out that the amygdala, a part of the brain involved in emotions and the "flight or fight response," responds more to blurry photos of faces depicting fear than unaltered or sharply detailed images.

At the same time, the part of our brain that recognizes faces is less engaged when the face is blurry. Cavanagh explains that this may mean we are more emotionally engaged when the detail-oriented part of our visual system is distracted, such as in Impressionist works where faces are unrealistically colorful or patchy.

Color vs. luminance

Artists also play with the difference between color and luminance. Most people have three kinds of cones in the eye's retina: red, blue and green. You know what color you're looking at because your brain compares the activities in two or three cones.

A different phenomenon, called luminance, adds the activities from the cones together as a measure of how much light appears to be passing through a given area. Usually when there is color contrast, there is also luminance contrast, but not always.

In the research of Margaret Livingstone, professor of neurobiology at Harvard University, she explored the painting "Impression Sunrise" by Claude Monet, which features a shimmering sun over water. Although the orange sun appears bright, it objectively has the same luminance as the background, Livingstone found. So why does it look so bright to the human eye? Livingstone explained in a 2009 lecture at the University of Michigan that there are two major processing streams for our visual system, which Livingstone calls the "what" and "where" streams. The "what" allows us to see in color and recognize faces and objects. The "where" is a faster and less detail-oriented but helps us navigate our environment but is insensitive to color.

When our brains recognize a color contrast but no light contrast, that's called "equal luminance," and it creates a sort of shimmering quality, Livingstone said. And that's what's going on in a Monet painting. Artists often play with luminance in order to give the illusion of three dimensions, since the range of luminance in real life is far greater than what can be portrayed in a painting, Livingstone said. By placing shadows and lights that wouldn't be present in real life, paintings are able to trick the eye into perceiving depth. In an icon by an artist of the Moscow School from about 1450, the Virgin Mary does not have a lot of depth.

For instance, medieval paintings portrayed the Virgin Mary in a dark blue dress, which makes her look flat. Leonardo da Vinci, however, revolutionized her appearance by adding extra lights to contrast with darks. The bottom line: To trick the brain into thinking something looks three-dimensional and lifelike, artists add elements -- lightness and shadows -- that wouldn't be present in real life but that tap into our hard-wired visual sensibilities.

Mona Lisa's smile

The Mona Lisa is undoubtedly one of the world's most famous paintings; the face of the woman in the painting is iconic. Da Vinci gave her facial expression a dynamic quality by playing with a discrepancy that exists in our peripheral and central vision systems, Livingstone says. The human visual system is organized such that the center of gaze is specialized for small, detailed things, and the peripheral vision has a lower resolution -- it's better at big, blurry things.

That's why, as your eyes move around the Mona Lisa's face, her expression appears to change, Livingstone says. The woman was painted such that, looking directly at the mouth, she appears to smile less than when you're staring into her eyes. When you look away from the mouth, your peripheral visual system picks up shadows from her cheeks that appear to extend the smile.

Photomosaics also take advantage of this difference between visual systems. With your peripheral visual system you might see a picture of a cat that's composed of individual photos of cats that are completely different.

Shadows and mirrors

From a scientific standpoint, it's possible to determine exactly how shadows are supposed to look based on the placements of light and how mirror reflections appear at given angles. But the brain doesn't perform such calculations naturally. It turns out that we don't really notice when shadows in paintings are unrealistically placed, unless glaringly so, or when mirrors don't work exactly the way they do in real life, Cavanagh explained in a 2005 article in "Nature."

Shadows are colored more darkly than what's around them; it's not readily apparent if the lighting direction is inconsistent. They can even be the wrong shape; as long as they don't look opaque, they help convince us of a three-dimensional figure. Studies have shown that people don't generally have a good working knowledge of how reflections should appear, or where, in relation to the original object, Cavanagh said. Paintings with people looking into mirrors or birds reflected in ponds have been fooling us for centuries.

Why we like art

There are certain aspects of art that seem universally appealing, regardless of the environment or culture in which you grew up, argues V.S. Ramachandran, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Diego. He discusses these ideas in his recent book "The Tell Tale Brain."

Symmetry, for instance, is widely considered to be beautiful. There's an evolutionary reason for that, he says: In the natural world, anything symmetrical is usually alive. Animals, for instance, have symmetrical shapes. That we find symmetry artistically appealing is probably based on a hard-wired system meant to alert us to the possibility of a living thing, he said.

Can you fool the brain? And then there's what Ramachandran calls the "peak shift principle." The basic idea is that animals attracted to a particular shape will be even more attracted to an exaggerated version of that form. This was shown in an experiment by Niko Tinbergen involving Herring seagull chicks. In a natural environment, the chick recognizes its mother by her beak. Mommy seagull beaks are yellow with a red spot at the end. So if you wave an isolated beak in front of a chick, it believes the disembodied beak is the mother and taps it as a way of asking to be fed. But even more striking, if you have a long yellow stick with a red stripe on it, the chick still begs for food. The red spot is the trigger that tells the chick this is the mother who will feed it. Now here's the crazy part: the chick is even more excited if the stick has multiple red stripes. The point of the seagull experiment is that although the actual mother's beak is attractive to the chick, a "super beak" that exaggerates the original beak hyperactivates a neural system. "I think you're seeing the same thing with all kinds of abstract art," Ramachandran said. "It looks distorted to the eye, but pleasing to the emotional center to the brain." In this self portrait, Vincent van Gogh distorts his own face with his signature style, which may increase its appeal.In other words, the distorted faces of famous artists such as Pablo Picasso and Gustav Klimt may be hyperactivating our neurons and drawing us in, so to speak. Impressionism, with its soft brushstrokes, is another form of distortion of familiar human and natural forms.

Further research

Can we know what is art? There's now a whole field called neuroesthetics devoted to the neural basis of why and how people appreciate art and music and what is beauty. Semir Zeki at University College London is credited with establishing this discipline, and says it's mushrooming.

Many scientists who study emotion are collaborating in this area. Zeki is studying why people tend prefer certain patterns of moving dots to others. Stanford Journal of Neuroscience: The Neuroscience of Art There have been several criticisms about neuroesthetics as a field.

Philosopher Alva Noe wrote in The New York Times last year that this branch of science has not produced any interesting or surprising insights, and that perhaps it won't because of the very nature of art itself -- how can anyone ever say definitively what it is?

Zeki said many challenges against his field are based on the false assumption that he and colleagues are trying to explain works of art. "We're not trying to explain any work of art," he said. "We're trying to use works of art to understand the brain."

Neuroscientists can make art, too. Zeki had works in an exhibit that opened last year in Italy called "White on White: Beyond Malevich." The series included white painted sculptures on white walls, illuminated by white light and color projections. With red and white light, the shadow of the object appears in the complimentary color -- green -- and the shadows change as your angle of vision changes. The biological basis for this complimentary color effect is not well understood, nor is the depth of shadow, which is also an illusion. So was Picasso right -- is art a lie? The description of Zeki's exhibition in Italy may highlight the truth: "Our purpose is to show how the brain reality even overrides the objective reality."

~~~~~~~

In my opinion: We tend to overanalyze...

Labels:

art,

the study of art

Tuesday, September 11, 2012

Friday, September 7, 2012

Where's My Memory? Laughing At Growing Older...

Please pause playlist at bottom of page to hear/watch video.

http://bcove.me/ld86hjjp

In his rendition of the classic Barbra Streisand hit "The Way We Were," two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist and animator Walt Handelsman takes a hilarious look at middle-age forgetfulness. "We have to be able to poke fun at ourselves," says Handelsman. "You can wring your hands about your lapses of memory, or you can say, 'Hey, this is it!' Be happy that you're growing older, that you're maturing, that you're smarter, that you're wiser. Plus, all of your friends are growing older with you. "So let's have some fun with it!"

http://bcove.me/ld86hjjp

In his rendition of the classic Barbra Streisand hit "The Way We Were," two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist and animator Walt Handelsman takes a hilarious look at middle-age forgetfulness. "We have to be able to poke fun at ourselves," says Handelsman. "You can wring your hands about your lapses of memory, or you can say, 'Hey, this is it!' Be happy that you're growing older, that you're maturing, that you're smarter, that you're wiser. Plus, all of your friends are growing older with you. "So let's have some fun with it!"

Friday, August 31, 2012

Sunday, August 26, 2012

Neil Alden Armstrong (August 5, 1930 – August 25, 2012)

Please pause playlist at bottom of page to watch/hear video.

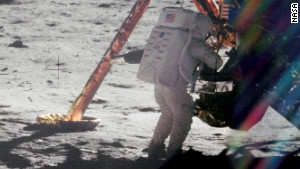

(CNN) -- Neil Armstrong, the American astronaut who made "one giant leap for mankind" when he became the first man to walk on the moon, died Saturday. He was 82.

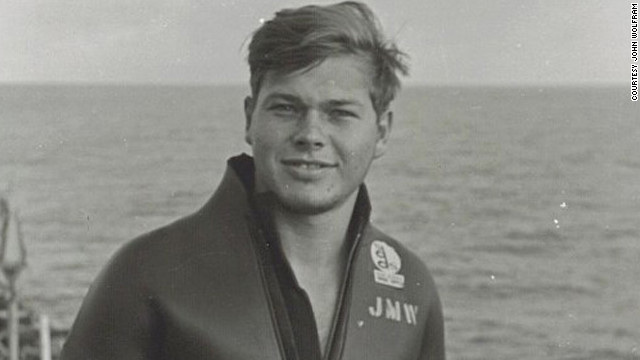

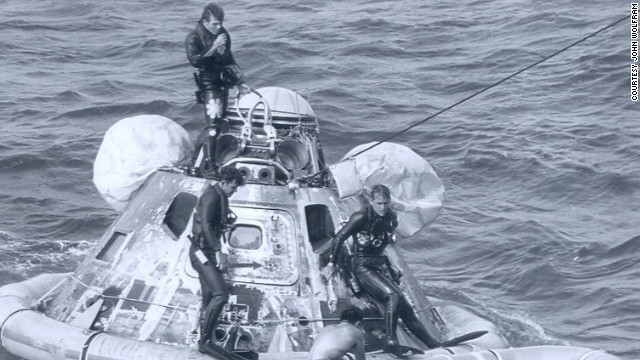

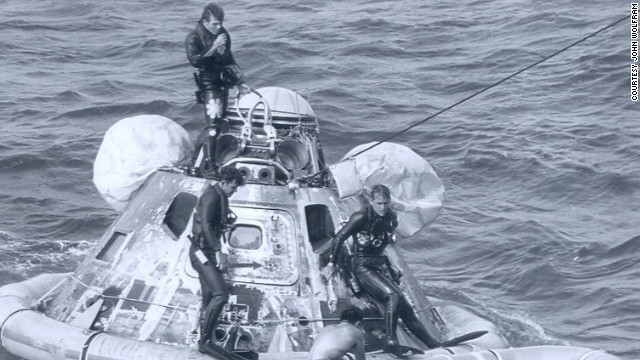

Navy SEALs Wes Chesser, left, and John Wolfram pause after securing the Apollo 11 capsule on July 24, 1969. Wolfram wore 60s "Flower Power" decals, showing his rebellious side. Chesser says, that only now does he realize how physically demanding the mission was. "We were in such good shape."

Navy SEALs Wes Chesser, left, and John Wolfram pause after securing the Apollo 11 capsule on July 24, 1969. Wolfram wore 60s "Flower Power" decals, showing his rebellious side. Chesser says, that only now does he realize how physically demanding the mission was. "We were in such good shape."

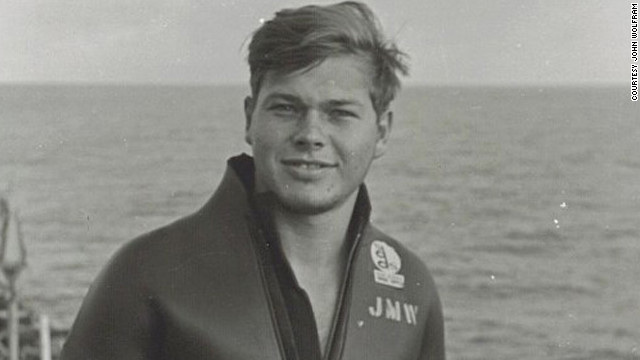

At age 20, only two years out of high school, Wolfram was the youngest of an elite team responsible for safely getting the Apollo 11 crew from their capsule to a helicopter. "Being the first to look them in the eye and see that they're OK -- it's quite a rush," Wolfram told CNN.

At age 20, only two years out of high school, Wolfram was the youngest of an elite team responsible for safely getting the Apollo 11 crew from their capsule to a helicopter. "Being the first to look them in the eye and see that they're OK -- it's quite a rush," Wolfram told CNN.

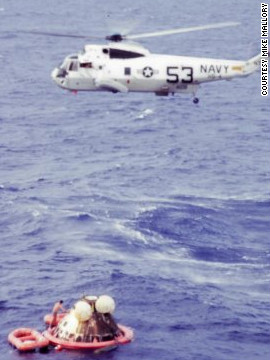

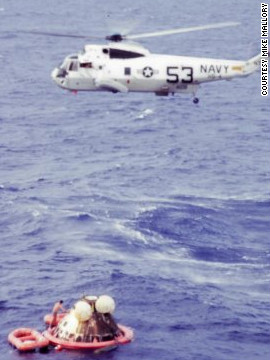

In this U.S. Navy photo, Apollo 11 splashes down about 1,000 miles off Hawaii. It was the exact moment when America achieved President Kennedy's goal to land a man on the moon and return him to Earth, says Scott Carmichael, author of "Moon Men Return." "It's one thing to get the astronauts to the moon, but you've got to bring them back alive."

In this U.S. Navy photo, Apollo 11 splashes down about 1,000 miles off Hawaii. It was the exact moment when America achieved President Kennedy's goal to land a man on the moon and return him to Earth, says Scott Carmichael, author of "Moon Men Return." "It's one thing to get the astronauts to the moon, but you've got to bring them back alive."

Carmichael described the capsule as "a bobbing, 12-foot high, 12,000-pound, spinning, behemoth" drifting across the ocean current. Frogman Mike Mallory, who snapped many photos of the mission, says he and Wolfram were "muscle guys" who worked against the waves and wind to pull an inflatable ring around the capsule.

Carmichael described the capsule as "a bobbing, 12-foot high, 12,000-pound, spinning, behemoth" drifting across the ocean current. Frogman Mike Mallory, who snapped many photos of the mission, says he and Wolfram were "muscle guys" who worked against the waves and wind to pull an inflatable ring around the capsule.

After the capsule was stabilized, the astronauts and SEALs put on biological isolation garments to guard against possible lunar pathogens. If the SEALs had been been directly exposed to the astronauts, they would have been ordered to be quarantined.

After the capsule was stabilized, the astronauts and SEALs put on biological isolation garments to guard against possible lunar pathogens. If the SEALs had been been directly exposed to the astronauts, they would have been ordered to be quarantined.

In the "decontamination raft" mission leader Clancy Hatleberg sprayed the astronauts with sodium hypochlorite and helped them scrub their suits.

In the "decontamination raft" mission leader Clancy Hatleberg sprayed the astronauts with sodium hypochlorite and helped them scrub their suits.

Hatleberg helped the astronauts climb into a "Billy-Pugh net" which was used to hoist them into a Navy chopper hovering above.

Hatleberg helped the astronauts climb into a "Billy-Pugh net" which was used to hoist them into a Navy chopper hovering above.

Astronaut Neil Armstrong was hoisted first into a hovering chopper, then Michael Collins, then Buzz Aldrin. Once aboard, the chopper headed for the USS Hornet. "There was real delight on those astronauts' faces, and a real thrill of accomplishment," says Wolfram.

Astronaut Neil Armstrong was hoisted first into a hovering chopper, then Michael Collins, then Buzz Aldrin. Once aboard, the chopper headed for the USS Hornet. "There was real delight on those astronauts' faces, and a real thrill of accomplishment," says Wolfram.

Aboard the aircraft carrier, the trio spoke with President Nixon from inside a trailer where they would be quarantined without incident for 21 days. "I saw you bouncing around in that boat out there," Nixon told them. "I wonder if that wasn't the hardest part of the journey." Armstrong, left, replied, "It was one of the hardest parts."

Aboard the aircraft carrier, the trio spoke with President Nixon from inside a trailer where they would be quarantined without incident for 21 days. "I saw you bouncing around in that boat out there," Nixon told them. "I wonder if that wasn't the hardest part of the journey." Armstrong, left, replied, "It was one of the hardest parts."

Back at the capsule, Wolfram and Hatleberg, right, flashed peace signs for Mallory's camera -- which raised eyebrows at the height of the Vietnam War. But Wolfram heard nothing about it from his superiors. "John was a wild, crazy guy," said Mallory. "That was his thing."

Back at the capsule, Wolfram and Hatleberg, right, flashed peace signs for Mallory's camera -- which raised eyebrows at the height of the Vietnam War. But Wolfram heard nothing about it from his superiors. "John was a wild, crazy guy," said Mallory. "That was his thing."

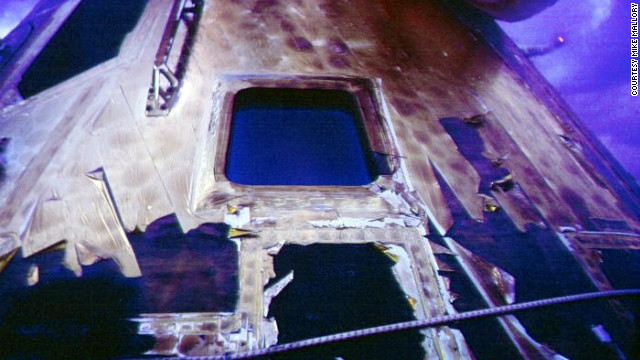

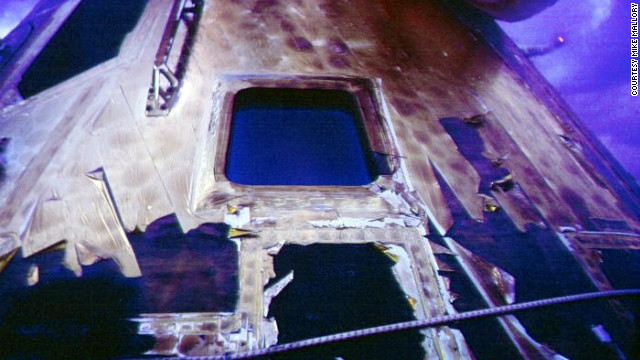

The capsule hatch was locked and sealed before the spacecraft was hoisted aboard the Hornet and kept in its own quarantine area, just in case. "We all took strips of that gold foil as souvenirs," said Wolfram.

The capsule hatch was locked and sealed before the spacecraft was hoisted aboard the Hornet and kept in its own quarantine area, just in case. "We all took strips of that gold foil as souvenirs," said Wolfram.

After two tours in Vietnam, Wolfram returned to the U.S. and had an epiphany during a church service. "That night, my life changed," he says. Now a Georgia-based husband, father and ordained minister, Wolfram serves as a missionary in Southeast Asia.

After two tours in Vietnam, Wolfram returned to the U.S. and had an epiphany during a church service. "That night, my life changed," he says. Now a Georgia-based husband, father and ordained minister, Wolfram serves as a missionary in Southeast Asia.

Wolfram details his adventure in his memoir, "Splashdown." He recently took his family to Washington's Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum where the Apollo 11 capsule is on display.

Wolfram details his adventure in his memoir, "Splashdown." He recently took his family to Washington's Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum where the Apollo 11 capsule is on display.

Mallory, now a husband and grandfather in Michigan, says he was just proud to be a part of the space program as a member of SEAL Team Swim 2. "I wish the space program was continuing better than it is." Chesser, a retired defense contractor, is a newlywed and grandfather living in Virginia. The Space Race "was an extremely exciting time for our country," Chesser says. "Today we don't have that."

Mallory, now a husband and grandfather in Michigan, says he was just proud to be a part of the space program as a member of SEAL Team Swim 2. "I wish the space program was continuing better than it is." Chesser, a retired defense contractor, is a newlywed and grandfather living in Virginia. The Space Race "was an extremely exciting time for our country," Chesser says. "Today we don't have that."

1

1

2

2

3

3

4

4

5

5

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

Apollo 11: The Recovery

Apollo 11: The Recovery

(CNN) -- Neil Armstrong, the American astronaut who made "one giant leap for mankind" when he became the first man to walk on the moon, died Saturday. He was 82.

"We are heartbroken to share the news that Neil Armstrong has passed away following complications resulting from cardiovascular procedures," Armstrong's family said in a statement.

Armstrong underwent heart surgery this month.

"While we mourn the loss of a very good man, we also celebrate his remarkable life and hope that it serves as an example to young people around the world to work hard to make their dreams come true, to be willing to explore and push the limits, and to selflessly serve a cause greater than themselves," his family said.

Navy SEALs Wes Chesser, left, and John Wolfram pause after securing the Apollo 11 capsule on July 24, 1969. Wolfram wore 60s "Flower Power" decals, showing his rebellious side. Chesser says, that only now does he realize how physically demanding the mission was. "We were in such good shape."

Navy SEALs Wes Chesser, left, and John Wolfram pause after securing the Apollo 11 capsule on July 24, 1969. Wolfram wore 60s "Flower Power" decals, showing his rebellious side. Chesser says, that only now does he realize how physically demanding the mission was. "We were in such good shape."

At age 20, only two years out of high school, Wolfram was the youngest of an elite team responsible for safely getting the Apollo 11 crew from their capsule to a helicopter. "Being the first to look them in the eye and see that they're OK -- it's quite a rush," Wolfram told CNN.

At age 20, only two years out of high school, Wolfram was the youngest of an elite team responsible for safely getting the Apollo 11 crew from their capsule to a helicopter. "Being the first to look them in the eye and see that they're OK -- it's quite a rush," Wolfram told CNN.

In this U.S. Navy photo, Apollo 11 splashes down about 1,000 miles off Hawaii. It was the exact moment when America achieved President Kennedy's goal to land a man on the moon and return him to Earth, says Scott Carmichael, author of "Moon Men Return." "It's one thing to get the astronauts to the moon, but you've got to bring them back alive."

In this U.S. Navy photo, Apollo 11 splashes down about 1,000 miles off Hawaii. It was the exact moment when America achieved President Kennedy's goal to land a man on the moon and return him to Earth, says Scott Carmichael, author of "Moon Men Return." "It's one thing to get the astronauts to the moon, but you've got to bring them back alive."

Carmichael described the capsule as "a bobbing, 12-foot high, 12,000-pound, spinning, behemoth" drifting across the ocean current. Frogman Mike Mallory, who snapped many photos of the mission, says he and Wolfram were "muscle guys" who worked against the waves and wind to pull an inflatable ring around the capsule.

Carmichael described the capsule as "a bobbing, 12-foot high, 12,000-pound, spinning, behemoth" drifting across the ocean current. Frogman Mike Mallory, who snapped many photos of the mission, says he and Wolfram were "muscle guys" who worked against the waves and wind to pull an inflatable ring around the capsule.

After the capsule was stabilized, the astronauts and SEALs put on biological isolation garments to guard against possible lunar pathogens. If the SEALs had been been directly exposed to the astronauts, they would have been ordered to be quarantined.

After the capsule was stabilized, the astronauts and SEALs put on biological isolation garments to guard against possible lunar pathogens. If the SEALs had been been directly exposed to the astronauts, they would have been ordered to be quarantined.

In the "decontamination raft" mission leader Clancy Hatleberg sprayed the astronauts with sodium hypochlorite and helped them scrub their suits.

In the "decontamination raft" mission leader Clancy Hatleberg sprayed the astronauts with sodium hypochlorite and helped them scrub their suits.

Hatleberg helped the astronauts climb into a "Billy-Pugh net" which was used to hoist them into a Navy chopper hovering above.

Hatleberg helped the astronauts climb into a "Billy-Pugh net" which was used to hoist them into a Navy chopper hovering above.

Aboard the aircraft carrier, the trio spoke with President Nixon from inside a trailer where they would be quarantined without incident for 21 days. "I saw you bouncing around in that boat out there," Nixon told them. "I wonder if that wasn't the hardest part of the journey." Armstrong, left, replied, "It was one of the hardest parts."

Aboard the aircraft carrier, the trio spoke with President Nixon from inside a trailer where they would be quarantined without incident for 21 days. "I saw you bouncing around in that boat out there," Nixon told them. "I wonder if that wasn't the hardest part of the journey." Armstrong, left, replied, "It was one of the hardest parts."

Back at the capsule, Wolfram and Hatleberg, right, flashed peace signs for Mallory's camera -- which raised eyebrows at the height of the Vietnam War. But Wolfram heard nothing about it from his superiors. "John was a wild, crazy guy," said Mallory. "That was his thing."

Back at the capsule, Wolfram and Hatleberg, right, flashed peace signs for Mallory's camera -- which raised eyebrows at the height of the Vietnam War. But Wolfram heard nothing about it from his superiors. "John was a wild, crazy guy," said Mallory. "That was his thing."

The capsule hatch was locked and sealed before the spacecraft was hoisted aboard the Hornet and kept in its own quarantine area, just in case. "We all took strips of that gold foil as souvenirs," said Wolfram.

The capsule hatch was locked and sealed before the spacecraft was hoisted aboard the Hornet and kept in its own quarantine area, just in case. "We all took strips of that gold foil as souvenirs," said Wolfram.

After two tours in Vietnam, Wolfram returned to the U.S. and had an epiphany during a church service. "That night, my life changed," he says. Now a Georgia-based husband, father and ordained minister, Wolfram serves as a missionary in Southeast Asia.

After two tours in Vietnam, Wolfram returned to the U.S. and had an epiphany during a church service. "That night, my life changed," he says. Now a Georgia-based husband, father and ordained minister, Wolfram serves as a missionary in Southeast Asia.

Wolfram details his adventure in his memoir, "Splashdown." He recently took his family to Washington's Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum where the Apollo 11 capsule is on display.

Wolfram details his adventure in his memoir, "Splashdown." He recently took his family to Washington's Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum where the Apollo 11 capsule is on display.

Mallory, now a husband and grandfather in Michigan, says he was just proud to be a part of the space program as a member of SEAL Team Swim 2. "I wish the space program was continuing better than it is." Chesser, a retired defense contractor, is a newlywed and grandfather living in Virginia. The Space Race "was an extremely exciting time for our country," Chesser says. "Today we don't have that."

Mallory, now a husband and grandfather in Michigan, says he was just proud to be a part of the space program as a member of SEAL Team Swim 2. "I wish the space program was continuing better than it is." Chesser, a retired defense contractor, is a newlywed and grandfather living in Virginia. The Space Race "was an extremely exciting time for our country," Chesser says. "Today we don't have that."

Apollo 11: The recovery mission

Navy SEAL John Wolfram

Splashdown!

The capsule after re-entry

Guarding against lunar pathogens

Decontamination raft

Hoisting the astronauts

Capsule, chopper, aircraft carrier

Quarantine

Peace signs

Capsule in quarantine

Life of ministry

Reunion

SEAL Team Swim 2

HIDE CAPTION

<<

<

>

>>

Apollo 11: The Recovery

Apollo 11: The Recovery

"As long as there are history books, Neil Armstrong will be included in them," said Charles Bolden. "As we enter this next era of space exploration, we do so standing on the shoulders of Neil Armstrong. We mourn the passing of a friend, fellow astronaut and true American hero."

Armstrong took two trips into space. He made his first journey in 1966 as commander of the Gemini 8 mission, which nearly ended in disaster.

Armstrong kept his cool and brought the spacecraft home safely after a thruster rocket malfunctioned and caused it to spin wildly out of control.

During his next space trip in July 1969, Armstrong and fellow astronauts Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins blasted off in Apollo 11 on a nearly 250,000-mile journey to the moon that went down in the history books. It took them four days to reach their destination.

The world watched and waited as the lunar module "Eagle" separated from the command module and began its descent.

Then came the words from Armstrong: "Tranquility Base here, the Eagle has landed."

About six and a half hours later at 10:56 p.m. ET on July 20, 1969, Armstrong, at age 38, became the first person to set foot on the moon.

He uttered the now-famous phrase: "That's one small step for (a) man, one giant leap for mankind."

The quote was originally recorded without the "a," which was picked up by voice recognition software many years later.

Armstrong was on the moon's surface for two hours and 32 minutes and Aldrin, who followed him, spent about 15 minutes less than that.

The two astronauts set up an American flag, scooped up moon rocks and set up scientific experiments before returning to the main spacecraft.

All three returned home to a hero's welcome, and none ever returned to space.

The moon landing was a major victory for the United States, which at the height of the Cold War in 1961 committed itself to landing a man on the moon and returning him safely before the decade was out.

It was also a defining moment for the world. The launch and landing were broadcast on live TV and countless people watched in amazement as Armstrong walked on the moon.

"I remember very clearly being an 8-year-old kid and watching the TV ... I remember even as a kid thinking, 'Wow, the world just changed,'" said astronaut Leroy Chiao. "And then hours later watching Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin take the very first step of any humans on another planetary body. That kind of flipped the switch for me in my head. I said, 'That's what I want to do, I want to be an astronaut.'"

Tributes to Armstrong -- who received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1969, the highest award offered to a U.S. civilian -- poured in as word of his death spread.

"Neil was among the greatest of American heroes -- not just of his time, but of all time," said President Barack Obama. "When he and his fellow crew members lifted off aboard Apollo 11 in 1969, they carried with them the aspirations of an entire nation. They set out to show the world that the American spirit can see beyond what seems unimaginable -- that with enough drive and ingenuity, anything is possible."

Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney said the former astronaut "today takes his place in the hall of heroes. With courage unmeasured and unbounded love for his country, he walked where man had never walked before. The moon will miss its first son of earth."

House Speaker John Boehner, from Ohio, said: "A true hero has returned to the Heavens to which he once flew. Neil Armstrong blazed trails not just for America, but for all of mankind. He inspired generations of boys and girls worldwide not just through his monumental feat, but with the humility and grace with which he carried himself to the end."

Armstrong was born in Wapakoneta, Ohio, on August 5, 1930. He was interested in flying even as a young boy, earning his pilot's license at age 16, studied aeronautical engineering and earned degrees from Purdue University and University of Southern California. He served in the Navy, and flew 78 combat missions during the Korean War.

"He was the best, and I will miss him terribly," said Collins, the Apollo 11 command module pilot.

After his historic mission to the moon, Armstrong worked for NASA, coordinating and managing the administration's research and technology work. In 1971, he resigned from NASA and taught engineering at the University of Cincinnati for nearly a decade.

While many people are quick to cash in on their 15 minutes of fame, Armstrong largely avoided the public spotlight and chose to lead a quiet, private life with his wife and children.

"He was really an engineer's engineer -- a modest man who was always uncomfortable in his singular role as the first person to set foot on the moon. He understood and appreciated the historic consequences of it and yet was never fully willing to embrace it. He was modest to the point of reclusive. You could call him the J.D. Salinger of the astronaut corps," said Miles O'Brien, an aviation expert with PBS' Newshour, formerly of CNN.

"He was a quiet, engaging, wonderful from the Midwest kind of guy. ... But when it came to the public exposure that was associated with this amazing accomplishment ... he ran from it. And part of it was he felt as if this was an accomplishment of many thousands of people. And it was. He took the lion's share of the credit and he felt uncomfortable with that," said O'Brien.

But Armstrong always recognized -- in a humble manner -- the importance of what he had accomplished.

"Looking back, we were really very privileged to live in that thin slice of history where we changed how man looks at himself and what he might become and where he might go," Armstrong said.

Labels:

astronaut,

moon,

neil armstrong

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.gif)